kind there were many in May and Jun this year) the granulations remain but little

disturbed to the very edge of the spot; and though only moderately elongated are seen

projecting a little over the edge of the umbra. The eruptive force has been too feeble to

drive them away and heap them up round the spot. They therefore continue much more nearly

in their normal condition.

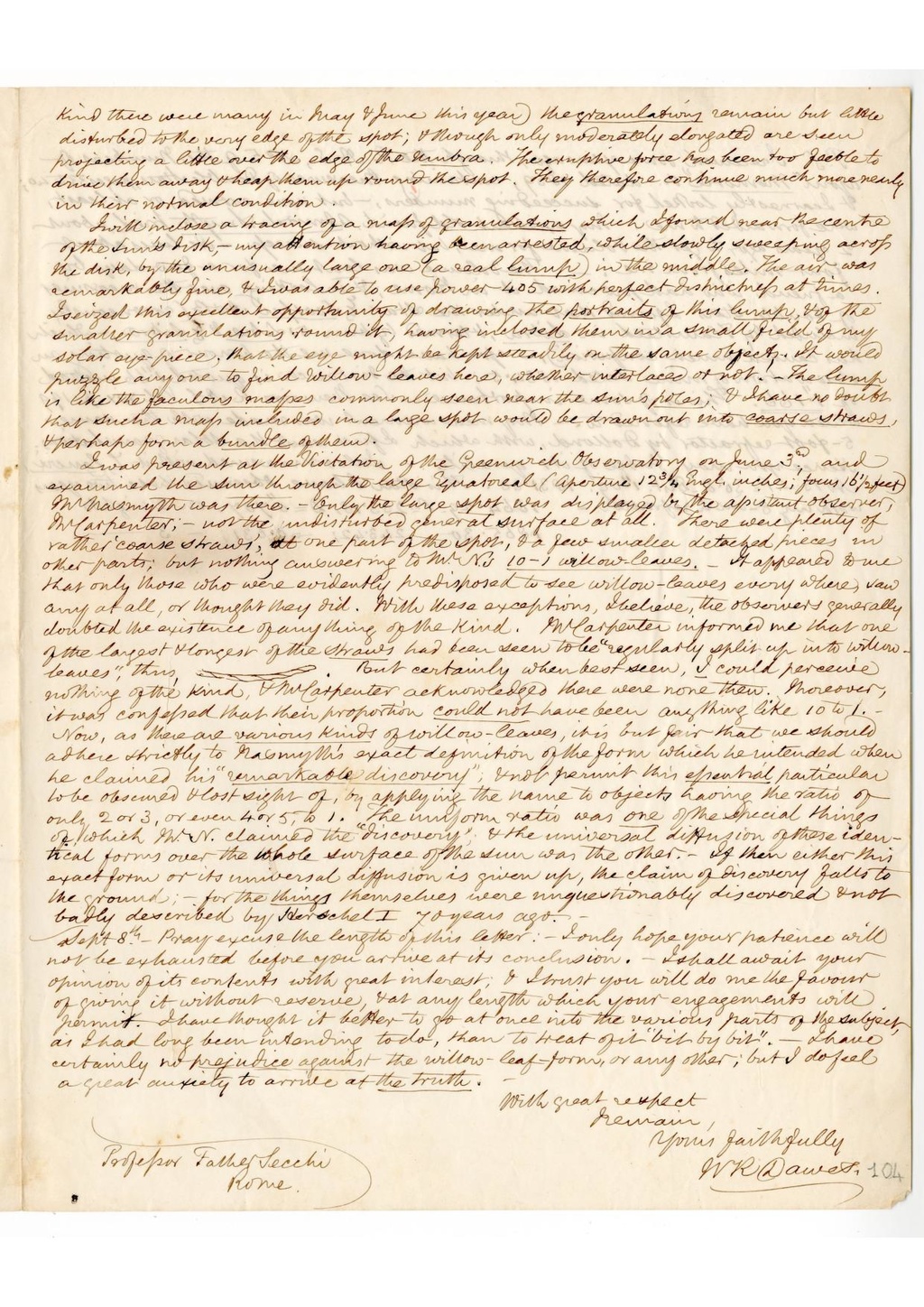

I will inclose a tracing of a mass of granulations which I found near the centre

of the Sun's disk,—my attention having been arrested, while slowly sweeping across

the disk, by the unusually large one (a real lump) in the middle. The air was

remarkably fine, and I was able to use power 405 with perfect distinctness at times.

I seized this excellent opportunity of drawing the portraits of this lump, and of the

smaller granulations round it, having inclosed them in a small field of my

solar eye-piece, that the eye might be kept steadily on the same objects. It would

puzzle any one to find willow-leaves here, whether interlaced or not.—The lump

is like the faculous masses commonly seen near the sun's poles; and I have no doubt

that such a mass included in a large spot would be drawn out into coarse straws,

and perhaps form a bundle of them.

I was present at the Visitation of the Greenwich Observatory on June 3rd, and

examined the sun through the large Equatoreal (aperture 12¾ Engl. inches; focus 16½ feet)

Mr. Nasmyth was there.—Only the large spot was displayed by the assistant observer,

Mr. Carpenter;—not the undisturbed general surface at all. There were plenty of

rather 'coarse straws', at one part of the spot, and a few smaller detached pieces in

other parts; but nothing answering to Mr. N.'s 10-1 willow-leaves.—It appeared to me

that only those who were evidently predisposed to see willow-leaves every where, saw

any at all, or thought they did. With these exceptions, I believe, the observers generally

doubted the existence of any thing of the kind. Mr. Carpenter informed me that one

of the largest and longest of the straws had been seen to be "regularly split up into willow-

leaves", thus, . But certainly when best seen, I could perceive

nothing of the kind, and Mr. Carpenter acknowledged there were none then. Moreover,

it was confessed that their proportion could not have been anything like 10 to 1.—

Now, as there are various kinds of willow-leaves, it is but fair that we should

adhere strictly to Nasmyth's exact definition of the form which he intended when

he claimed his "remarkable discovery"; and not permit this essential particular

to be obscured and lost sight of, by applying the name to objects having the ratio of

only 2 or 3, or even 4 or 5, to 1. The uniform ratio was one of the special things

of which Mr. N. claimed the "discover:' and the universal diffusion of these iden-

tical forms over the whole surface of the sun was the other.—If then either this

exact form or its universal diffusion is given up, the claim of discovery falls to

the ground;—for the things themselves were unquestionably discovered and not

badly described by Herschel I 70 years ago.—

Sept. 8th.—Pray excuse the length of this letter:—I only hope your patience will

not be exhausted before you arrive at its conclusion.—I shall await your

opinion of its contents with great interest; and I trust you will do me the favour of giving it without reserve, and at any length which your engagements will

permit. I have thought it better to go at once into the various parts of the subject,

as I had long been intending to do, than to treat of it "bit by bit".—I have

certainly no prejudice against the willow-leaf-form, or any other; but I do feel

a great anxiety to arrive at the truth.—

With great respect

I remain,

Yours faithfully

WR Dawes

Page:ASC 1865 09 06 13-52.pdf/5

From GATE

Revision as of 03:30, 20 September 2020 by Maria Sermersheim (talk | contribs)

This page has not been proofread