Difference between revisions of "Novitas"

| (25 intermediate revisions by 2 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| + | <div style="text-align:justify"> | ||

| + | <center>''''Válgase de su novedad, que mientras fuere nuevo, será estimado''''. (Gracián)</center> | ||

<tabber> | <tabber> | ||

English= | English= | ||

| + | |||

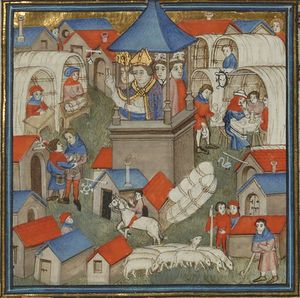

[[File:Bénédiction-de-la-Foire-du-Lendit.jpg|thumb|Bénédiction de la Foire du Lendit]] | [[File:Bénédiction-de-la-Foire-du-Lendit.jpg|thumb|Bénédiction de la Foire du Lendit]] | ||

By the beginning of the 1600s the ''Jahrmarkt'' ( yearly Fair) becomes an essential hub of commercial exchange. These fairs , which are known to exist from the 12th century, usually took place after Sunday mass, and were therefore called ''Masses''. The most famous of these fairs was the one held in the [https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Foires_de_Champagne Champagne] region. This semantic shift will progress alongside with the growing interest in these events, to the point that they became independent from the religious occasions they were originally tied to. The fair location will move from near the cathedral’s square, to the space outside the city walls. These markets will gradually turn into "novelty fairs", in order to satisfy, in some ways, people’s desire for novelty and curiosity. Here follows a Sixteenth century description of the Strasbourg fair: | By the beginning of the 1600s the ''Jahrmarkt'' ( yearly Fair) becomes an essential hub of commercial exchange. These fairs , which are known to exist from the 12th century, usually took place after Sunday mass, and were therefore called ''Masses''. The most famous of these fairs was the one held in the [https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Foires_de_Champagne Champagne] region. This semantic shift will progress alongside with the growing interest in these events, to the point that they became independent from the religious occasions they were originally tied to. The fair location will move from near the cathedral’s square, to the space outside the city walls. These markets will gradually turn into "novelty fairs", in order to satisfy, in some ways, people’s desire for novelty and curiosity. Here follows a Sixteenth century description of the Strasbourg fair: | ||

<blockquote class="templatequote"> | <blockquote class="templatequote"> | ||

| − | <p style="font-size: | + | <p style="font-size:100%;text-align:left">... ''Its twenty-two thousand inhabitants would open their doors twice a year, in order to welcome about a hundred thousand visitors to the fair. People arrived by ship, carriage or on foot; they came from London, Antwerp, Lyon and Venice, but also from the neighboring villages and every time, for three weeks, they transformed the life of the entire city. As in a gigantic bazaar, the streets and squares, the houses and convents as well, raised admiration for the amount of human skill involved: crafts of the highest quality, the most recent technical inventions, exotic goods from overseas, paintings, erudite and topical books such as the "new gazettes", which were exhibited or sung by their very same authors.''<ref>K. Kroll, ''Körperbegabung versus Verkörperung. Das Verhältnis und Geist im frühneuzeitlichen Jahrmarktspektakel'' in Erika Fischer-Lichte, Christian Hornund Matthias Warstat (ed) ''Verkörperung'', 2001, p. 37. </ref></p> |

</blockquote><br> | </blockquote><br> | ||

| − | The historian might be interested in the emergence of this systemic compulsion for novelty. In fact, while during the 16th and 17th century religious or political communication viewed novelty as something adventurous, the commercial environment greatly appreciated it, to the point that it will become a driving force for interchange. Gradually, religious and political systems will turn their negative judgment into associating novelty with something virtuous and even necessary. The impression is that markets tended to easily absorb uncertainty and variability, and exploited these conditions in order to influence supply and demand. Whereas, the religious system mainly associated uncertainty with its threatening features, while positing equilibrium and stability as values. Novelty seems to have a special connection with information. | + | The historian might be interested in the emergence of this systemic compulsion for novelty. In fact, while during the 16th and 17th century religious or political communication viewed novelty as something adventurous, the commercial environment greatly appreciated it, to the point that it will become a driving force for interchange. Gradually, religious and political systems will turn their negative judgment into associating novelty with something virtuous and even necessary. The impression is that markets tended to easily absorb uncertainty and variability, and exploited these conditions in order to influence supply and demand. Whereas, the religious system mainly associated uncertainty with its threatening features, while positing equilibrium and stability as values. Novelty seems to have a special connection with information. |

Information is displayed on the tables of the fairs where the [https://www.museogalileo.it/istituto/mostre-virtuali/vespucci/iconografia/nova_reperta.html ''nova reperta''] (new findings) are highly valued, but it is also shouted by sellers of the "new gazettes". These first means of diffusion are not so much concentrated on the truthfulness the information, with all its polemogenic aspects, but on its core subject, identified as a difference that makes a difference <ref>Bateson, G. | Information is displayed on the tables of the fairs where the [https://www.museogalileo.it/istituto/mostre-virtuali/vespucci/iconografia/nova_reperta.html ''nova reperta''] (new findings) are highly valued, but it is also shouted by sellers of the "new gazettes". These first means of diffusion are not so much concentrated on the truthfulness the information, with all its polemogenic aspects, but on its core subject, identified as a difference that makes a difference <ref>Bateson, G. | ||

''Verso un’ecologia della mente'', 1993, Adelphi, Milano.</ref>. Information, in order to be considered such, must be new. Before anything, all news have to be "fresh". An extreme, and nevertheless exemplary case of disunity among truth and information, is that of the 16th century "war of the news", which involved the Republic of Ragusa, Venice and the Turk. <br> | ''Verso un’ecologia della mente'', 1993, Adelphi, Milano.</ref>. Information, in order to be considered such, must be new. Before anything, all news have to be "fresh". An extreme, and nevertheless exemplary case of disunity among truth and information, is that of the 16th century "war of the news", which involved the Republic of Ragusa, Venice and the Turk. <br> | ||

| Line 15: | Line 18: | ||

<blockquote class="templatequote"> | <blockquote class="templatequote"> | ||

| − | <p style="font-size: | + | <p style="font-size:100%;text-align:left">''According to what the librarian told me about buying large number of books at the fairs, merchants don’t have time to read them, therefore don’t really know their contents. From a glimpse at the inscription they are able to tell whether the books are new, and that is enough for getting them to travel in order to buy them: for the novelties alone, of which the English are especially curious''. ''[[Page:EBC_1608_09_20_0798.pdf/2|Nuncio of Cologne to Robert Bellarmine, 20 September 1608]]''</p> |

</blockquote><lb/> | </blockquote><lb/> | ||

| − | Gradually, the contents will have to be presented under the guise of innovation, one would say today. This way, innovation will slowly open the way to appearing as a normal tendency that presupposes an expectation of progress and future. Information is an indicator of this angst for novelty, that excludes repetition upon which knowledge was based. In this sense, we are faced with an epochal transformation of knowledge. Going after the novelties, at the urgent pace of constantly seeking fresh news, implies the alteration of the Mediaeval rhythm of reading, and therefore of learning: ''Aiunt enim multum legendum esse, non multa'' (Pliny the Younger, ''Epist''. 7,9). Here there may be a reversal of depth in favor of superficiality. According to one epistemological tradition, knowledge implied going beyond what appears on the surface, whereas the increasing growth of information imposes the ability to orientate quickly, in order to maintain one’s self afloat and establish as many connections as possible. The appearance in printed texts, of indexes, tables and marginalia might be considered a witness to this change, with the aim of providing the reader with guidance tools. This transformation also suggests a change in the understanding of the concept of time, by which the present no longer represents the eternity of God in all presents, but only the instant that determines the difference between past and future. | + | Gradually, the contents will have to be presented under the guise of innovation, one would say today. This way, innovation will slowly open the way to appearing as a normal tendency that presupposes an expectation of progress and future. Information is an indicator of this angst for novelty, that excludes repetition upon which knowledge was based. In this sense, we are faced with an epochal transformation of knowledge. Going after the novelties, at the urgent pace of constantly seeking fresh news, implies the alteration of the Mediaeval rhythm of reading, and therefore of learning: ''Aiunt enim multum legendum esse, non multa'' (Pliny the Younger, ''Epist''. 7,9). |

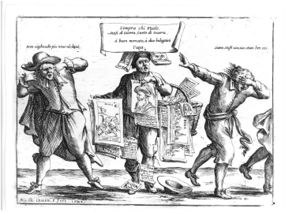

| − | + | [[File:Compra chi vuole news.jpg|thumb|''Compra chi vuole'', Giuseppe Maria Mitelli (1684)]]Here there may be a reversal of depth in favor of superficiality. According to one epistemological tradition, knowledge implied going beyond what appears on the surface, whereas the increasing growth of information imposes the ability to orientate quickly, in order to maintain one’s self afloat and establish as many connections as possible. The appearance in printed texts, of indexes, tables and marginalia might be considered a witness to this change, with the aim of providing the reader with guidance tools. This transformation also suggests a change in the understanding of the concept of time, by which the present no longer represents the eternity of God in all presents, but only the instant that determines the difference between past and future. | |

<blockquote class="templatequote"> | <blockquote class="templatequote"> | ||

| − | <p style="font-size: | + | <p style="font-size:100%;text-align:left"> |

| − | The effect of this semantic race with regards to what is new, is not recognized in the form of conceptualization, but in those changes concerning the idea of the present where only what is new can be new -. Now the present is no longer the presence of the eternity of time, nor the situation in which - in view of the salvation of the soul - one can decide for or against sin. Present is nothing but what makes the difference between past and future.<ref>Luhmann. N., ''La sociedad de la sociedad''. México, 2006, p. 796. </ref> </p></blockquote><br> | + | ''The effect of this semantic race with regards to what is new, is not recognized in the form of conceptualization, but in those changes concerning the idea of the present where only what is new can be new -. Now the present is no longer the presence of the eternity of time, nor the situation in which - in view of the salvation of the soul - one can decide for or against sin. Present is nothing but what makes the difference between past and future''.<ref>Luhmann. N., ''La sociedad de la sociedad''. México, 2006, p. 796. </ref> </p></blockquote><br> |

The evolution of the concept of ''novitas'' is the sign of a semantic catastrophe; catastrophe in its etymological meaning (καταστρέφω = "overturn") of abrupt quality change produced by a gradual and continuous evolution. The volcanic eruption can well represent this type of evolution, when it causes new geological and environmental situations that, in turn, open the way to a new kind of stability. Catastrophe, conceived as such, never holds a univocal meaning: some may see "destruction" in it, others may see "opportunities".<br> | The evolution of the concept of ''novitas'' is the sign of a semantic catastrophe; catastrophe in its etymological meaning (καταστρέφω = "overturn") of abrupt quality change produced by a gradual and continuous evolution. The volcanic eruption can well represent this type of evolution, when it causes new geological and environmental situations that, in turn, open the way to a new kind of stability. Catastrophe, conceived as such, never holds a univocal meaning: some may see "destruction" in it, others may see "opportunities".<br> | ||

| Line 31: | Line 34: | ||

{{Citations/Link}} | {{Citations/Link}} | ||

==Florilegium== | ==Florilegium== | ||

| − | * ''Gran hechizo es el de la novedad, que como todo lo tenemos tan visto, pagámonos de juguetes nuevos, así de la naturaleza como del arte, haciendo vulgares agravios a los antiguos prodigios por conocidos: lo que ayer fue un pasmo, hoy viene a ser desprecio, no porque haya perdido de su perfección, sino de nuestra estimación; no porque se haya mudado, antes porque no, y porque se nos hace de nuevo. Redimen esta civilidad del gusto los sabios con hacer reflexiones nuevas sobre las perfecciones antiguas, renovando el gusto con la admiración.'' <ref>Gracián, [https://es.wikisource.org/wiki/El_Criticón._Primera_parte:_Crisi_3 ''El Criticón, crisis III''.] </ref | + | * <p>''Gran hechizo es el de la novedad, que como todo lo tenemos tan visto, pagámonos de juguetes nuevos, así de la naturaleza como del arte, haciendo vulgares agravios a los antiguos prodigios por conocidos: lo que ayer fue un pasmo, hoy viene a ser desprecio, no porque haya perdido de su perfección, sino de nuestra estimación; no porque se haya mudado, antes porque no, y porque se nos hace de nuevo. Redimen esta civilidad del gusto los sabios con hacer reflexiones nuevas sobre las perfecciones antiguas, renovando el gusto con la admiración.''</p> <ref>Gracián, [https://es.wikisource.org/wiki/El_Criticón._Primera_parte:_Crisi_3 ''El Criticón, crisis III''.] </ref> |

* ''Válgase de su novedad, que mientras fuere nuevo, será estimado.''<ref>Gracián, ''[http://www.biblioteca.org.ar/libros/131939.pdf Oráculo manual y arte de prudencia]'', 269. </ref><p></p> | * ''Válgase de su novedad, que mientras fuere nuevo, será estimado.''<ref>Gracián, ''[http://www.biblioteca.org.ar/libros/131939.pdf Oráculo manual y arte de prudencia]'', 269. </ref><p></p> | ||

| − | *''[A] Io scuserei volentieri il nostro popolo di non avere altro modello né altra regola di perfezione che i propri costumi e le proprie usanze: infatti è vizio comune non del volgo soltanto, ma di quasi tutti gli uomini, di mirare alla maniera di vivere in cui sono nati e limitarsi ad essa. Mi sta bene che questo popolo, vedendo Fabrizio o Lelio, trovi barbari il loro contegno e il loro portamento, poiché non sono vestiti né acconciati alla nostra moda. Ma mi rammarico della sua singolare mancanza di discernimento nel lasciarsi a tal punto ingannare e accecare dall’autorità dell’uso attuale, da esser capace di cambiar parere e opinione tutti i mesi, se così piace alla moda; e da dare giudizi così disparati su se stesso. Quando si portava la stecca del giustacuore alta sul petto, si sosteneva con argomenti fervorosi che quello era il suo posto; qualche anno dopo, ecco la stecca discesa fino alle cosce: ci si burla dell’altra usanza, la si trova scomoda e insopportabile. L’attuale maniera di vestirsi fa immediatamente condannare l’antica, con una risolutezza così grande e un consenso così generale, che direste che è una specie di mania che stravolge in tal modo il cervello. Poiché il nostro cambiamento in questo è così pronto e improvviso che l’inventiva di tutti i sarti del mondo non saprebbe fornire sufficienti novità, è giocoforza che molto spesso le fogge disprezzate tornino in credito, e poco dopo cadano di nuovo in disprezzo; e che uno stesso giudizio adotti, nello spazio di quindici o vent’anni, due o tre opinioni non solo diverse, ma contrarie, con un’incostanza e una leggerezza incredibili. [C] Non c’è nessuno fra noi tanto accorto da non lasciarsi intrappolare in questa contraddizione, e abbarbagliare così la vista interna come quella esterna senza accorgersene''.<lb/> <ref>Montaigne, Michel de., ''Saggi'', a cura di Fausta Garavini e André Tournon, 2012, Milano, Lib. I, Cap. XLIX, ''Dei costumi antichi''.</ref><p>< | + | *<p>''[A] Io scuserei volentieri il nostro popolo di non avere altro modello né altra regola di perfezione che i propri costumi e le proprie usanze: infatti è vizio comune non del volgo soltanto, ma di quasi tutti gli uomini, di mirare alla maniera di vivere in cui sono nati e limitarsi ad essa. Mi sta bene che questo popolo, vedendo Fabrizio o Lelio, trovi barbari il loro contegno e il loro portamento, poiché non sono vestiti né acconciati alla nostra moda. Ma mi rammarico della sua singolare mancanza di discernimento nel lasciarsi a tal punto ingannare e accecare dall’autorità dell’uso attuale, da esser capace di cambiar parere e opinione tutti i mesi, se così piace alla moda; e da dare giudizi così disparati su se stesso. Quando si portava la stecca del giustacuore alta sul petto, si sosteneva con argomenti fervorosi che quello era il suo posto; qualche anno dopo, ecco la stecca discesa fino alle cosce: ci si burla dell’altra usanza, la si trova scomoda e insopportabile. L’attuale maniera di vestirsi fa immediatamente condannare l’antica, con una risolutezza così grande e un consenso così generale, che direste che è una specie di mania che stravolge in tal modo il cervello. Poiché il nostro cambiamento in questo è così pronto e improvviso che l’inventiva di tutti i sarti del mondo non saprebbe fornire sufficienti novità, è giocoforza che molto spesso le fogge disprezzate tornino in credito, e poco dopo cadano di nuovo in disprezzo; e che uno stesso giudizio adotti, nello spazio di quindici o vent’anni, due o tre opinioni non solo diverse, ma contrarie, con un’incostanza e una leggerezza incredibili. [C] Non c’è nessuno fra noi tanto accorto da non lasciarsi intrappolare in questa contraddizione, e abbarbagliare così la vista interna come quella esterna senza accorgersene''.<lb/> <ref>Montaigne, Michel de., ''Saggi'', a cura di Fausta Garavini e André Tournon, 2012, Milano, Lib. I, Cap. XLIX, ''Dei costumi antichi''.</ref></p> |

| − | + | *<p>''Mi trovavo or ora su quel passo dove Plutarco dice di se stesso che mentre Rustico assisteva a una sua orazione a Roma, ricevette un plico da parte dell’imperatore e indugiò ad aprirlo finché tutto fu finito: per cui (egli dice) tutti i presenti lodarono straordinariamente la gravità di quel personaggio. Invero, poiché egli stava parlando della curiosità, e di quella passione avida e golosa di notizie che ci fa abbandonare qualsiasi cosa con tanta indiscrezione e impazienza per occuparci di un nuovo venuto, e perdere ogni rispetto e ogni ritegno per dissuggellare subito, dovunque ci troviamo, le lettere che ci sono state portate, ha avuto ragione di lodare la gravità di Rustico; e poteva anche aggiungervi la lode della sua educazione e cortesia per non aver voluto interrompere il corso dell’orazione.''<ref>Montaigne, Michel de., ''Saggi'', a cura di Fausta Garavini e André Tournon, 2012, Milano, Lib. II, Cap. IV, ''A domani gli affari'' .</ref></p> | |

| − | + | *<p>''Il gazzettiere si corica tranquillo a sera con una notizia che, alteratasi nella notte, è costretto ad abbandonare al suo risveglio.''<ref>Jean de la Bruyère; ''Les Caractères ou Les Mœurs de ce Siècle'', 33.</ref><lb/></p> | |

| − | + | * <p>'''[Varietas]''''' Furthermore, great is the dissension very often among the Greek codices which are now held in hand; whence also those who in our times say they dedicate themselves to explaining the Latin texts based on the Greek, not rarely disagree among themselves not only in words but also in meanings. And what's more, these new interpreters do not interpret the same copies with the same meaning! For the fourth verse of Psalm 109 was translated differently by Luther, differently by Pomeranus, differently by Pelicanus, differently by Bucerus, differently by Munster, differently by Zwingli, differently by Felix, differently by Pagninus, so that now the editions of Theodotion, Symmachus, Aquila, the fifth, likewise the sixth and seventh editions, and also the Vulgate of the Septuagint, seem to me very few in number if we compare them to the countless ones of these men. And what's more, Erasmus does not agree with himself! For there exists a fifth edition, and a sixth would also exist, if he had not feared having a mark of inconstancy branded upon himself or if he had not been intercepted by death. But certainly this '''variety of versions''' has always been, as it were, a '''characteristic and peculiar trait of heretics'''. But moreover, we ought to reject and fear '''variety''' much more, as I said before, which is clearly an enemy of constancy and unity. Virtues which the Church cannot possess if there is not the same unity and consensus of Scripture. In this regard, our ages are more fortunate than the ancient ones. For formerly, almost as many copies were published as there were codices. But now, without doubt by the special providence of the Holy Spirit, by the solicitude of Damasus, by the very great labors of Jerome, the Holy Church has received a harmonious unity of the Scriptures, and all variety, having been removed from the midst, is a single Latin edition received by the consensus of all. Wherefore, those who refer us back to the Greek copies wish to introduce the same variety from which Jerome formerly defended our books, indeed the same falsity from which he purged our codices. For the variety of codices is accustomed to be an easy occasion for corruption. And even if there is no corruption, variety itself is nevertheless harmful. For that which is different can never be asserted to be true, as Jerome wrote to Domnio and Rogatian and to Damasus: «That which varies», he says, «is not true, even the testimony of the wicked confirms this.» For if, he says, faith is to be given to the Latin copies, let those answer who have almost as many copies as codices. Therefore, the variety of the Latin copies which existed then detracted from the credibility of such copies.'' | |

| + | </p><ref>Melchor Cano, ''[https://juanbeldaplans.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/introduc-general.pdf De locis Theologicis]''</ref> | ||

== References == | == References == | ||

<references /> | <references /> | ||

| Line 45: | Line 49: | ||

Italian= | Italian= | ||

[[File:Bénédiction-de-la-Foire-du-Lendit.jpg|thumb|Bénédiction de la Foire du Lendit]] | [[File:Bénédiction-de-la-Foire-du-Lendit.jpg|thumb|Bénédiction de la Foire du Lendit]] | ||

| − | A partire dal cinquecento le ''Jahrmarkt'' (fiere dell'anno) si convertiranno in nodi basilari per lo scambio commerciale. Molte di queste fiere già presenti nel XII secolo, perché organizzate dopo la messa domenicale, si denominarono anche ''Messe''. La più importante di queste fiere è stata quella della contea della [https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Foires_de_Champagne Champagne]. Questo spostamento semantico andrà di pari passo con una crescente centralità di queste manifestazioni al punto di soppiantare e diventare autonome dagli eventi religiosi ai quali in origine erano legate. Man mano si sposteranno dai pressi della piazza della cattedrale per celebrarsi fuori dalla cinta muraria. Questi mercati si convertiranno in "fiere delle novità" e soddisfano, in qualche modo, una sete di novità e curiosità. Così un testo sulla fiera a Strasburgo nel XVI secolo: | + | <div style="text-align:justify">A partire dal cinquecento le ''Jahrmarkt'' (fiere dell'anno) si convertiranno in nodi basilari per lo scambio commerciale. Molte di queste fiere già presenti nel XII secolo, perché organizzate dopo la messa domenicale, si denominarono anche ''Messe''. La più importante di queste fiere è stata quella della contea della [https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Foires_de_Champagne Champagne]. Questo spostamento semantico andrà di pari passo con una crescente centralità di queste manifestazioni al punto di soppiantare e diventare autonome dagli eventi religiosi ai quali in origine erano legate. Man mano si sposteranno dai pressi della piazza della cattedrale per celebrarsi fuori dalla cinta muraria. Questi mercati si convertiranno in "fiere delle novità" e soddisfano, in qualche modo, una sete di novità e curiosità. Così un testo sulla fiera a Strasburgo nel XVI secolo: |

<blockquote class="templatequote"> | <blockquote class="templatequote"> | ||

| − | <p style="font-size: | + | <p style="font-size:100%;text-align:left">... ''i ventiduemila abitanti aprivano due volte l'anno le loro porte per accogliere all'incirca centomila visitatori della fiera. Questi arrivano in nave, in carrozza o a piedi; giungevano da Londra, Anversa, Lione e Venezia, ma anche dai villaggi vicini della regione e ogni volta, per tre settimane, trasformavano l'intera vita della città. Come in un gigantesco bazar per strade e piazze, nelle case e persino nei conventi si poteva ammirare sorpreso quanto l'abilità umana aveva fabbricato: i prodotti più scelti dell'artigianato, le invenzioni tecniche più recenti, merci esotiche d'oltremare, dipinti, libri dotti e di attualità come le «nuove gazzette» che venivano esposte o cantate dai loro stessi autori''.<ref>K. Kroll, ''Körperbegabung versus Verkörperung. Das Verhältnis und Geist im frühneuzeitlichen Jahrmarktspektakel'' in Erika Fischer-Lichte, Christian Hornund Matthias Warstat (ed) ''Verkörperung'', 2001, p. 37. </ref>.</p> |

</blockquote><lb/> | </blockquote><lb/> | ||

Allo storico potrebbe interessare l'emergenza di questa costrizione sistemica alla novità, davanti alla quale la comunicazione religiosa o politica dei secoli XVI e XVII vedrà in essa qualcosa di temerario mentre nell'ambito commerciale sarà d'allora apprezzata al punto tale da essere considerata un motore per l'interscambio. Gradualmente i sistemi religioso e politico invertiranno la loro valutazione negativa per associare alla novità un qualcosa di virtuoso e di necessario. Da l'impressione che i mercati abbiano assorbito più facilmente l'incertezza e la variabilità e sfruttino queste condizioni per muovere l'offerta e la domanda. Invece, per il sistema religioso l'incertezza è percepita solo nei suoi aspetti minacciosi e postula l'equilibrio e la stabilità come valori.<lb/> | Allo storico potrebbe interessare l'emergenza di questa costrizione sistemica alla novità, davanti alla quale la comunicazione religiosa o politica dei secoli XVI e XVII vedrà in essa qualcosa di temerario mentre nell'ambito commerciale sarà d'allora apprezzata al punto tale da essere considerata un motore per l'interscambio. Gradualmente i sistemi religioso e politico invertiranno la loro valutazione negativa per associare alla novità un qualcosa di virtuoso e di necessario. Da l'impressione che i mercati abbiano assorbito più facilmente l'incertezza e la variabilità e sfruttino queste condizioni per muovere l'offerta e la domanda. Invece, per il sistema religioso l'incertezza è percepita solo nei suoi aspetti minacciosi e postula l'equilibrio e la stabilità come valori.<lb/> | ||

| Line 57: | Line 61: | ||

A partire dal XVII secolo alcuni libri scientifici includeranno nei loro titoli la parola ''novus''<ref>Si veda a questo riguardo Cevolini, A., ''De Arte Excerpendi. Imparare a dimenticare nella modernità'', 2006, p. 54 e ss.</ref>. All'interno della corrispondenza di Bellarmino può notarsi questa costrizione a selezionare "novità": | A partire dal XVII secolo alcuni libri scientifici includeranno nei loro titoli la parola ''novus''<ref>Si veda a questo riguardo Cevolini, A., ''De Arte Excerpendi. Imparare a dimenticare nella modernità'', 2006, p. 54 e ss.</ref>. All'interno della corrispondenza di Bellarmino può notarsi questa costrizione a selezionare "novità": | ||

<blockquote class="templatequote"> | <blockquote class="templatequote"> | ||

| − | <p style="font-size: | + | <p style="font-size:100%;text-align:left">''Oltre che come mi disse il libraro quando si comprano libri alle fiere in gran numero, i mercanti non hanno tempo di leggerli per intendere ciò che contengono, anzi basta loro di veder dall'iscrizione che sono libri nuovi per muoversi a comprarli per la sola novità de la quale in particolare gli Inglesi sono curiosissimi''. ''[[Page:EBC_1608_09_20_0798.pdf/2|Il nunzio di Cologna a Roberto Bellarmino, 20 settembre 1608]]''</p> |

</blockquote><lb/> | </blockquote><lb/> | ||

Gradualmente i contenuti si dovranno presentare sotto la veste dell'innovazione, si direbbe oggi. L'innovazione così si aprirà lentamente la strada fino ad apparire come una tendenza normale che presuppone una attesa di progresso e di futuro. L'informazione è un indicatore di questa ansia di novità che esclude la ripetizione sulla quale si assicurava il sapere. In questo senso ci troviamo davanti a una trasformazione epocale della conoscenza. Perseguire le novità, al ritmo incalzante delle notizie sempre fresche, implicherà un'alterazione del ritmo della lettura medievale e pertanto dell'apprendimento: ''Aiunt enim multum legendum esse, non multa'' (Plinio il Giovane, ''Epist''. 7,9). Potrebbe evidenziarsi qui un capovolgimento della profondità in favore della superficialità. Se una certa tradizione epistemologica indicava che per comprendere era necessario andare al di là di ciò che appare in superficie, con il crescente aumento d'informazioni ci si dovrà orientare velocemente per riuscire a stare a galla ed stabilire il maggior numero di collegamenti possibili. Gli sviluppi di indici, tabelle e marginalia nei testi a stampa potrebbero testimoniare questo cambiamento per offrire al lettore strumenti di orientamento. Questa trasformazione parla anche di un mutamento del significato del tempo in virtù del quale il presente non rappresenterà più l'eternità di Dio in tutti i presenti ma soltanto l'istante che determina la differenza tra passato e futuro. | Gradualmente i contenuti si dovranno presentare sotto la veste dell'innovazione, si direbbe oggi. L'innovazione così si aprirà lentamente la strada fino ad apparire come una tendenza normale che presuppone una attesa di progresso e di futuro. L'informazione è un indicatore di questa ansia di novità che esclude la ripetizione sulla quale si assicurava il sapere. In questo senso ci troviamo davanti a una trasformazione epocale della conoscenza. Perseguire le novità, al ritmo incalzante delle notizie sempre fresche, implicherà un'alterazione del ritmo della lettura medievale e pertanto dell'apprendimento: ''Aiunt enim multum legendum esse, non multa'' (Plinio il Giovane, ''Epist''. 7,9). Potrebbe evidenziarsi qui un capovolgimento della profondità in favore della superficialità. Se una certa tradizione epistemologica indicava che per comprendere era necessario andare al di là di ciò che appare in superficie, con il crescente aumento d'informazioni ci si dovrà orientare velocemente per riuscire a stare a galla ed stabilire il maggior numero di collegamenti possibili. Gli sviluppi di indici, tabelle e marginalia nei testi a stampa potrebbero testimoniare questo cambiamento per offrire al lettore strumenti di orientamento. Questa trasformazione parla anche di un mutamento del significato del tempo in virtù del quale il presente non rappresenterà più l'eternità di Dio in tutti i presenti ma soltanto l'istante che determina la differenza tra passato e futuro. | ||

<blockquote class="templatequote"> | <blockquote class="templatequote"> | ||

| − | <p style="font-size: | + | <p style="font-size:100%;text-align:left"> ''L'effetto di questa corsa semantica di ciò che è nuovo non lo si riconosce nella forma della concettualizzazione ma nei cambiamenti riguardo l'idea di presente -nel quale soltanto ciò che è nuovo può essere nuovo-. Ora il presente non è più la presenza dell'eternità del tempo e nemmeno esclusivamente la situazione nella quale -in vista della salvezza dell'anima- si può decidere a favore o contro il peccato. Presente non è un altra cosa che la differenza tra passato e futuro.''<ref>Luhmann. N., ''La sociedad de la sociedad''. México, 2006, p. 796. </ref> </p></blockquote> |

<lb/>L'evoluzione del concetto di ''novitas'' sta a indicare una catastrofe semantica; catastrofe intesa, partendo dalla sua etimologia (καταστρέϕω="capovolgere"), come cambiamento qualitativo brusco, prodotto da un’ evoluzione graduale e continua. L'eruzione vulcanica può ben rappresentare questa evoluzione inaugurando nuove realtà geologiche e ambientali che si aprono a nuove stabilità. La catastrofe, così concepita, non ha mai un segno univoco: alcuni potrebbero osservare in essa "distruzione" altri "opportunità". <lb/> La novità, in quanto schema di osservazione, ha bisogno del contra-concetto di "vecchio". Una crescente valorizzazione degli antichi, dei classici, così come si è registrata per esempio a partire del Rinascimento, permetterà di creare degli spazi per la produzione di novità. Dopo la Rivoluzione Francese si consoliderà questa valorizzazione, utile anche a segnare la frontiera tra ''Ancien Régime'' e presente rivoluzionario in vista di un futuro inteso come progresso. | <lb/>L'evoluzione del concetto di ''novitas'' sta a indicare una catastrofe semantica; catastrofe intesa, partendo dalla sua etimologia (καταστρέϕω="capovolgere"), come cambiamento qualitativo brusco, prodotto da un’ evoluzione graduale e continua. L'eruzione vulcanica può ben rappresentare questa evoluzione inaugurando nuove realtà geologiche e ambientali che si aprono a nuove stabilità. La catastrofe, così concepita, non ha mai un segno univoco: alcuni potrebbero osservare in essa "distruzione" altri "opportunità". <lb/> La novità, in quanto schema di osservazione, ha bisogno del contra-concetto di "vecchio". Una crescente valorizzazione degli antichi, dei classici, così come si è registrata per esempio a partire del Rinascimento, permetterà di creare degli spazi per la produzione di novità. Dopo la Rivoluzione Francese si consoliderà questa valorizzazione, utile anche a segnare la frontiera tra ''Ancien Régime'' e presente rivoluzionario in vista di un futuro inteso come progresso. | ||

{{Citations/Link}} | {{Citations/Link}} | ||

| Line 70: | Line 74: | ||

*''[A] Io scuserei volentieri il nostro popolo di non avere altro modello né altra regola di perfezione che i propri costumi e le proprie usanze: infatti è vizio comune non del volgo soltanto, ma di quasi tutti gli uomini, di mirare alla maniera di vivere in cui sono nati e limitarsi ad essa. Mi sta bene che questo popolo, vedendo Fabrizio o Lelio, trovi barbari il loro contegno e il loro portamento, poiché non sono vestiti né acconciati alla nostra moda. Ma mi rammarico della sua singolare mancanza di discernimento nel lasciarsi a tal punto ingannare e accecare dall’autorità dell’uso attuale, da esser capace di cambiar parere e opinione tutti i mesi, se così piace alla moda; e da dare giudizi così disparati su se stesso. Quando si portava la stecca del giustacuore alta sul petto, si sosteneva con argomenti fervorosi che quello era il suo posto; qualche anno dopo, ecco la stecca discesa fino alle cosce: ci si burla dell’altra usanza, la si trova scomoda e insopportabile. L’attuale maniera di vestirsi fa immediatamente condannare l’antica, con una risolutezza così grande e un consenso così generale, che direste che è una specie di mania che stravolge in tal modo il cervello. Poiché il nostro cambiamento in questo è così pronto e improvviso che l’inventiva di tutti i sarti del mondo non saprebbe fornire sufficienti novità, è giocoforza che molto spesso le fogge disprezzate tornino in credito, e poco dopo cadano di nuovo in disprezzo; e che uno stesso giudizio adotti, nello spazio di quindici o vent’anni, due o tre opinioni non solo diverse, ma contrarie, con un’incostanza e una leggerezza incredibili. [C] Non c’è nessuno fra noi tanto accorto da non lasciarsi intrappolare in questa contraddizione, e abbarbagliare così la vista interna come quella esterna senza accorgersene''.<lb/> <ref>Montaigne, Michel de., ''Saggi'', a cura di Fausta Garavini e André Tournon, 2012, Milano, Lib. I, Cap. XLIX, ''Dei costumi antichi''.</ref><p></p> | *''[A] Io scuserei volentieri il nostro popolo di non avere altro modello né altra regola di perfezione che i propri costumi e le proprie usanze: infatti è vizio comune non del volgo soltanto, ma di quasi tutti gli uomini, di mirare alla maniera di vivere in cui sono nati e limitarsi ad essa. Mi sta bene che questo popolo, vedendo Fabrizio o Lelio, trovi barbari il loro contegno e il loro portamento, poiché non sono vestiti né acconciati alla nostra moda. Ma mi rammarico della sua singolare mancanza di discernimento nel lasciarsi a tal punto ingannare e accecare dall’autorità dell’uso attuale, da esser capace di cambiar parere e opinione tutti i mesi, se così piace alla moda; e da dare giudizi così disparati su se stesso. Quando si portava la stecca del giustacuore alta sul petto, si sosteneva con argomenti fervorosi che quello era il suo posto; qualche anno dopo, ecco la stecca discesa fino alle cosce: ci si burla dell’altra usanza, la si trova scomoda e insopportabile. L’attuale maniera di vestirsi fa immediatamente condannare l’antica, con una risolutezza così grande e un consenso così generale, che direste che è una specie di mania che stravolge in tal modo il cervello. Poiché il nostro cambiamento in questo è così pronto e improvviso che l’inventiva di tutti i sarti del mondo non saprebbe fornire sufficienti novità, è giocoforza che molto spesso le fogge disprezzate tornino in credito, e poco dopo cadano di nuovo in disprezzo; e che uno stesso giudizio adotti, nello spazio di quindici o vent’anni, due o tre opinioni non solo diverse, ma contrarie, con un’incostanza e una leggerezza incredibili. [C] Non c’è nessuno fra noi tanto accorto da non lasciarsi intrappolare in questa contraddizione, e abbarbagliare così la vista interna come quella esterna senza accorgersene''.<lb/> <ref>Montaigne, Michel de., ''Saggi'', a cura di Fausta Garavini e André Tournon, 2012, Milano, Lib. I, Cap. XLIX, ''Dei costumi antichi''.</ref><p></p> | ||

*''Mi trovavo or ora su quel passo dove Plutarco dice di se stesso che mentre Rustico assisteva a una sua orazione a Roma, ricevette un plico da parte dell’imperatore e indugiò ad aprirlo finché tutto fu finito: per cui (egli dice) tutti i presenti lodarono straordinariamente la gravità di quel personaggio. Invero, poiché egli stava parlando della curiosità, e di quella passione avida e golosa di notizie che ci fa abbandonare qualsiasi cosa con tanta indiscrezione e impazienza per occuparci di un nuovo venuto, e perdere ogni rispetto e ogni ritegno per dissuggellare subito, dovunque ci troviamo, le lettere che ci sono state portate, ha avuto ragione di lodare la gravità di Rustico; e poteva anche aggiungervi la lode della sua educazione e cortesia per non aver voluto interrompere il corso dell’orazione.''<ref>Montaigne, Michel de., ''Saggi'', a cura di Fausta Garavini e André Tournon, 2012, Milano, Lib. II, Cap. IV, ''A domani gli affari'' .</ref><p></p> | *''Mi trovavo or ora su quel passo dove Plutarco dice di se stesso che mentre Rustico assisteva a una sua orazione a Roma, ricevette un plico da parte dell’imperatore e indugiò ad aprirlo finché tutto fu finito: per cui (egli dice) tutti i presenti lodarono straordinariamente la gravità di quel personaggio. Invero, poiché egli stava parlando della curiosità, e di quella passione avida e golosa di notizie che ci fa abbandonare qualsiasi cosa con tanta indiscrezione e impazienza per occuparci di un nuovo venuto, e perdere ogni rispetto e ogni ritegno per dissuggellare subito, dovunque ci troviamo, le lettere che ci sono state portate, ha avuto ragione di lodare la gravità di Rustico; e poteva anche aggiungervi la lode della sua educazione e cortesia per non aver voluto interrompere il corso dell’orazione.''<ref>Montaigne, Michel de., ''Saggi'', a cura di Fausta Garavini e André Tournon, 2012, Milano, Lib. II, Cap. IV, ''A domani gli affari'' .</ref><p></p> | ||

| − | *''Il gazzettiere si corica tranquillo a sera con una notizia che, alteratasi nella notte, è costretto ad abbandonare al suo risveglio.''<ref>Jean de la Bruyère; ''Les Caractères ou Les Mœurs de ce Siècle'', 33.</ref> | + | *''Il gazzettiere si corica tranquillo a sera con una notizia che, alteratasi nella notte, è costretto ad abbandonare al suo risveglio.''<ref>Jean de la Bruyère; ''Les Caractères ou Les Mœurs de ce Siècle'', 33.</ref><lb/> |

| + | * '''[Varietas]''' <lb/> | ||

| + | ''Además, muy a menudo existe una gran discrepancia entre los códices griegos que ahora se manejan, de ahí que en nuestros tiempos incluso disienten entre sí no sólo en las palabras sino también en las ideas. ¿Cómo es, si no, que a veces esos nuevos traductores no traducen en el mismo sentido los mismos ejemplares? Pues el versículo cuarto del salmo 109 lo tradujeron de distinta manera Lutero, Pomerano, Pelicán, Buzero, Munster, Zuinglio, Félix, Pagnino, de modo que me parecen poquísimas en número la edición de Teodoción, Símaco, Aquila, la quinta, así como la sexta y la séptima y además la vulgata de los Setenta, si las comparas con las innumerables versiones de aquéllos''.<lb/> | ||

| + | ''¿Cómo es que Erasmo no está de acuerdo consigo mismo? Se conserva, en efecto, su quinta edición y se conservaría la sexta, si no hubiera temido que se le tachara de inconstancia o no hubiera sido impedido por la muerte. Y ciertamente esa variedad de versiones siempre fue para los herejes por así decir familiar y propia. [...] Así pues, esas personas inconstantes más que traducir las Sagradas Escrituras desde las fuentes, lo que hacen es traducirse a sí mismos en torno a las fuentes, e inducidos por diversas y peregrinas doctrinas fluctúan como niños pequeños y son llevados de una parte a otra por cualquier viento de doctrina. Y verdaderamente, cuando alguna '''novedad''' salta como un nuevo viento, enseguida se distingue el peso del grano y la ligereza de la paja, y entonces sin gran trabajo es sacudido fuera de la era lo que estaba dentro sin peso alguno''.<lb/> | ||

| + | ''También se debe temer del cambio [mutatio] mismo de las cosas, pues incluso pequeños movimientos son capaces de perturbar la situación común de los ciudadanos, de tal forma que si se cambiaran los compases musicales -como dice Platón- se produciría un cambio en la República y en las costumbres''.<lb/> | ||

| + | ''[...] debemos rechazar mucho más aún y temer esa '''variedad''', que es obviamente enemiga de la constancia y la unidad, virtudes que la Iglesia no puede tener si no se da a la par la unidad y el consenso de la Escritura. Bajo este aspecto son más afortunados nuestros tiempos que los antiguos, pues antiguamente se divulgaban tantos ejemplares como códices. Pero en cambio ahora, sin duda por peculiar providencia del Espíritu Santo, por la solicitud de Dámaso, por los esfuerzos extraordinarios de Jerónimo, la Santa Iglesia ha recibido la concorde unidad de las Escrituras y fue quitada de en medio toda variedad, mediante la recepción con el acuerdo de todos de una edición latina única''.<lb/> | ||

| + | <p>''Por esa razón, quienes nos remiten a los ejemplares griegos pretenden introducir la misma variedad, de la que antiguamente Jerónimo reivindicó nuestros libros, o más aún, la misma falsedad de la que aquél expurgó nuestros códices. Pues la variedad de códices suele ser ocasión fácil de corrupción. Y aunque ninguna corrupción se produjera, la variedad misma sin embargo es perjudicial, pues nunca puede decirse verdadero lo que es diverso, como escribió Jerónimo a Donenión y a Rogaciano; y, dirigiéndose a Dámaso, afirma: «Con el testimonio incluso de los maldicientes se comprueba que no es verdadero lo que varía. Si, en efecto, se ha de prestar fe a los ejem- plares latinos, que respondan aquellos que tienen casi tantos ejemplares como códices. Por consiguiente, la variedad de ejemplares latinos que entonces había quitaba el crédito en tales ejemplares»''.</p> | ||

| + | <ref>Melchor Cano, ''[https://juanbeldaplans.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/introduc-general.pdf De locis Theologicis]''. Lib. II, cap.13.</ref> | ||

== References == | == References == | ||

Latest revision as of 12:55, 29 April 2025

By the beginning of the 1600s the Jahrmarkt ( yearly Fair) becomes an essential hub of commercial exchange. These fairs , which are known to exist from the 12th century, usually took place after Sunday mass, and were therefore called Masses. The most famous of these fairs was the one held in the Champagne region. This semantic shift will progress alongside with the growing interest in these events, to the point that they became independent from the religious occasions they were originally tied to. The fair location will move from near the cathedral’s square, to the space outside the city walls. These markets will gradually turn into "novelty fairs", in order to satisfy, in some ways, people’s desire for novelty and curiosity. Here follows a Sixteenth century description of the Strasbourg fair:

... Its twenty-two thousand inhabitants would open their doors twice a year, in order to welcome about a hundred thousand visitors to the fair. People arrived by ship, carriage or on foot; they came from London, Antwerp, Lyon and Venice, but also from the neighboring villages and every time, for three weeks, they transformed the life of the entire city. As in a gigantic bazaar, the streets and squares, the houses and convents as well, raised admiration for the amount of human skill involved: crafts of the highest quality, the most recent technical inventions, exotic goods from overseas, paintings, erudite and topical books such as the "new gazettes", which were exhibited or sung by their very same authors.[1]

The historian might be interested in the emergence of this systemic compulsion for novelty. In fact, while during the 16th and 17th century religious or political communication viewed novelty as something adventurous, the commercial environment greatly appreciated it, to the point that it will become a driving force for interchange. Gradually, religious and political systems will turn their negative judgment into associating novelty with something virtuous and even necessary. The impression is that markets tended to easily absorb uncertainty and variability, and exploited these conditions in order to influence supply and demand. Whereas, the religious system mainly associated uncertainty with its threatening features, while positing equilibrium and stability as values. Novelty seems to have a special connection with information.

Information is displayed on the tables of the fairs where the nova reperta (new findings) are highly valued, but it is also shouted by sellers of the "new gazettes". These first means of diffusion are not so much concentrated on the truthfulness the information, with all its polemogenic aspects, but on its core subject, identified as a difference that makes a difference [2]. Information, in order to be considered such, must be new. Before anything, all news have to be "fresh". An extreme, and nevertheless exemplary case of disunity among truth and information, is that of the 16th century "war of the news", which involved the Republic of Ragusa, Venice and the Turk.

Between the end of the 14th century and mid 16th century, the tiny Republic of Ragusa became the centre of heavy information activity, which granted her a strategic medium role between The Republic and the Empire. The Republic offered novelle (news) about the Venetian galleys to the kings of Naples, and afterwards to Charles V and the pope. Ragusa will do the same with the doge, offering him some turchesca on the movements of the Turkish ships. After the battle of Mohàcs (1526), the victory of Suleiman I over the Hungarians implied a power increase of the Ottoman empire. Thus, Ragusa will start to inform the Turks more efficiently about the naval movements of the West. The Rector of Ragusa severely prohibited private informants, thus creating an actual monopoly of information. More than a form of communication, information converted itself into an actual commodity, in order to control the movements of The Republic: Non bene pro toto libertas venditur auro; if freedom cannot be sold, not even for all the gold in the world, it can perhaps be obtained in exchange for information.

Now, this whirlwind of novelty was neither created by the ability of the gazetteers [4], nor by the sheets of nine, or by the need to know the Turk’s moves in advance, and not even by the same press. The thirst for novelty, which is emphasized by the success enjoyed by information, is a symptom of the epochal change of a social system that evolves from an internal hierarchical differentiation, towards a functionally differentiated society. In this phase, the press represents the evolutionary factor at its own service and, in a situation of progressive differentiation, finds the opportunity for its own development. From the 17th century, some of the scientific books will start to include the word novus into their titles [5]. In Bellarmine’s correspondence, there is a reference to this slavery to novelties:

According to what the librarian told me about buying large number of books at the fairs, merchants don’t have time to read them, therefore don’t really know their contents. From a glimpse at the inscription they are able to tell whether the books are new, and that is enough for getting them to travel in order to buy them: for the novelties alone, of which the English are especially curious. Nuncio of Cologne to Robert Bellarmine, 20 September 1608

Gradually, the contents will have to be presented under the guise of innovation, one would say today. This way, innovation will slowly open the way to appearing as a normal tendency that presupposes an expectation of progress and future. Information is an indicator of this angst for novelty, that excludes repetition upon which knowledge was based. In this sense, we are faced with an epochal transformation of knowledge. Going after the novelties, at the urgent pace of constantly seeking fresh news, implies the alteration of the Mediaeval rhythm of reading, and therefore of learning: Aiunt enim multum legendum esse, non multa (Pliny the Younger, Epist. 7,9).

Here there may be a reversal of depth in favor of superficiality. According to one epistemological tradition, knowledge implied going beyond what appears on the surface, whereas the increasing growth of information imposes the ability to orientate quickly, in order to maintain one’s self afloat and establish as many connections as possible. The appearance in printed texts, of indexes, tables and marginalia might be considered a witness to this change, with the aim of providing the reader with guidance tools. This transformation also suggests a change in the understanding of the concept of time, by which the present no longer represents the eternity of God in all presents, but only the instant that determines the difference between past and future.

The effect of this semantic race with regards to what is new, is not recognized in the form of conceptualization, but in those changes concerning the idea of the present where only what is new can be new -. Now the present is no longer the presence of the eternity of time, nor the situation in which - in view of the salvation of the soul - one can decide for or against sin. Present is nothing but what makes the difference between past and future.[6]

The evolution of the concept of novitas is the sign of a semantic catastrophe; catastrophe in its etymological meaning (καταστρέφω = "overturn") of abrupt quality change produced by a gradual and continuous evolution. The volcanic eruption can well represent this type of evolution, when it causes new geological and environmental situations that, in turn, open the way to a new kind of stability. Catastrophe, conceived as such, never holds a univocal meaning: some may see "destruction" in it, others may see "opportunities".

Novelties, as an observational scheme, needs the counter-concept of "old". A growing appreciation of the ancients, and of the classical studies, as it has been recorded since the Renaissance, for example, will generate areas for the production of novelties. This appreciation will consolidate after the French Revolution. It is useful also to mark the frontier between Ancien Régime and revolutionary present in view of a future understood as progress.

Florilegium

Gran hechizo es el de la novedad, que como todo lo tenemos tan visto, pagámonos de juguetes nuevos, así de la naturaleza como del arte, haciendo vulgares agravios a los antiguos prodigios por conocidos: lo que ayer fue un pasmo, hoy viene a ser desprecio, no porque haya perdido de su perfección, sino de nuestra estimación; no porque se haya mudado, antes porque no, y porque se nos hace de nuevo. Redimen esta civilidad del gusto los sabios con hacer reflexiones nuevas sobre las perfecciones antiguas, renovando el gusto con la admiración.

[7]- Válgase de su novedad, que mientras fuere nuevo, será estimado.[8]

[A] Io scuserei volentieri il nostro popolo di non avere altro modello né altra regola di perfezione che i propri costumi e le proprie usanze: infatti è vizio comune non del volgo soltanto, ma di quasi tutti gli uomini, di mirare alla maniera di vivere in cui sono nati e limitarsi ad essa. Mi sta bene che questo popolo, vedendo Fabrizio o Lelio, trovi barbari il loro contegno e il loro portamento, poiché non sono vestiti né acconciati alla nostra moda. Ma mi rammarico della sua singolare mancanza di discernimento nel lasciarsi a tal punto ingannare e accecare dall’autorità dell’uso attuale, da esser capace di cambiar parere e opinione tutti i mesi, se così piace alla moda; e da dare giudizi così disparati su se stesso. Quando si portava la stecca del giustacuore alta sul petto, si sosteneva con argomenti fervorosi che quello era il suo posto; qualche anno dopo, ecco la stecca discesa fino alle cosce: ci si burla dell’altra usanza, la si trova scomoda e insopportabile. L’attuale maniera di vestirsi fa immediatamente condannare l’antica, con una risolutezza così grande e un consenso così generale, che direste che è una specie di mania che stravolge in tal modo il cervello. Poiché il nostro cambiamento in questo è così pronto e improvviso che l’inventiva di tutti i sarti del mondo non saprebbe fornire sufficienti novità, è giocoforza che molto spesso le fogge disprezzate tornino in credito, e poco dopo cadano di nuovo in disprezzo; e che uno stesso giudizio adotti, nello spazio di quindici o vent’anni, due o tre opinioni non solo diverse, ma contrarie, con un’incostanza e una leggerezza incredibili. [C] Non c’è nessuno fra noi tanto accorto da non lasciarsi intrappolare in questa contraddizione, e abbarbagliare così la vista interna come quella esterna senza accorgersene.

[9]Mi trovavo or ora su quel passo dove Plutarco dice di se stesso che mentre Rustico assisteva a una sua orazione a Roma, ricevette un plico da parte dell’imperatore e indugiò ad aprirlo finché tutto fu finito: per cui (egli dice) tutti i presenti lodarono straordinariamente la gravità di quel personaggio. Invero, poiché egli stava parlando della curiosità, e di quella passione avida e golosa di notizie che ci fa abbandonare qualsiasi cosa con tanta indiscrezione e impazienza per occuparci di un nuovo venuto, e perdere ogni rispetto e ogni ritegno per dissuggellare subito, dovunque ci troviamo, le lettere che ci sono state portate, ha avuto ragione di lodare la gravità di Rustico; e poteva anche aggiungervi la lode della sua educazione e cortesia per non aver voluto interrompere il corso dell’orazione.[10]

Il gazzettiere si corica tranquillo a sera con una notizia che, alteratasi nella notte, è costretto ad abbandonare al suo risveglio.[11]

[Varietas] Furthermore, great is the dissension very often among the Greek codices which are now held in hand; whence also those who in our times say they dedicate themselves to explaining the Latin texts based on the Greek, not rarely disagree among themselves not only in words but also in meanings. And what's more, these new interpreters do not interpret the same copies with the same meaning! For the fourth verse of Psalm 109 was translated differently by Luther, differently by Pomeranus, differently by Pelicanus, differently by Bucerus, differently by Munster, differently by Zwingli, differently by Felix, differently by Pagninus, so that now the editions of Theodotion, Symmachus, Aquila, the fifth, likewise the sixth and seventh editions, and also the Vulgate of the Septuagint, seem to me very few in number if we compare them to the countless ones of these men. And what's more, Erasmus does not agree with himself! For there exists a fifth edition, and a sixth would also exist, if he had not feared having a mark of inconstancy branded upon himself or if he had not been intercepted by death. But certainly this variety of versions has always been, as it were, a characteristic and peculiar trait of heretics. But moreover, we ought to reject and fear variety much more, as I said before, which is clearly an enemy of constancy and unity. Virtues which the Church cannot possess if there is not the same unity and consensus of Scripture. In this regard, our ages are more fortunate than the ancient ones. For formerly, almost as many copies were published as there were codices. But now, without doubt by the special providence of the Holy Spirit, by the solicitude of Damasus, by the very great labors of Jerome, the Holy Church has received a harmonious unity of the Scriptures, and all variety, having been removed from the midst, is a single Latin edition received by the consensus of all. Wherefore, those who refer us back to the Greek copies wish to introduce the same variety from which Jerome formerly defended our books, indeed the same falsity from which he purged our codices. For the variety of codices is accustomed to be an easy occasion for corruption. And even if there is no corruption, variety itself is nevertheless harmful. For that which is different can never be asserted to be true, as Jerome wrote to Domnio and Rogatian and to Damasus: «That which varies», he says, «is not true, even the testimony of the wicked confirms this.» For if, he says, faith is to be given to the Latin copies, let those answer who have almost as many copies as codices. Therefore, the variety of the Latin copies which existed then detracted from the credibility of such copies.

References

- ↑ K. Kroll, Körperbegabung versus Verkörperung. Das Verhältnis und Geist im frühneuzeitlichen Jahrmarktspektakel in Erika Fischer-Lichte, Christian Hornund Matthias Warstat (ed) Verkörperung, 2001, p. 37.

- ↑ Bateson, G. Verso un’ecologia della mente, 1993, Adelphi, Milano.

- ↑ Jean de la Bruyère; Les Caractères ou Les Mœurs de ce Siècle, 33.

- ↑ On the "gazzetta" origins see Infelise, Mario; Gazzetta. Storia di una parola; 2017, Venezia.

- ↑ See Cevolini, A., De Arte Excerpendi. Imparare a dimenticare nella modernità, 2006, p. 54 e ss.

- ↑ Luhmann. N., La sociedad de la sociedad. México, 2006, p. 796.

- ↑ Gracián, El Criticón, crisis III.

- ↑ Gracián, Oráculo manual y arte de prudencia, 269.

- ↑ Montaigne, Michel de., Saggi, a cura di Fausta Garavini e André Tournon, 2012, Milano, Lib. I, Cap. XLIX, Dei costumi antichi.

- ↑ Montaigne, Michel de., Saggi, a cura di Fausta Garavini e André Tournon, 2012, Milano, Lib. II, Cap. IV, A domani gli affari .

- ↑ Jean de la Bruyère; Les Caractères ou Les Mœurs de ce Siècle, 33.

- ↑ Melchor Cano, De locis Theologicis

The text of this page has been reviewed and approved by the Lexicon of modernity (ISBN: 9788878393950 ; DOI: 10.5281/zenodo.1483194) editorial board.

Cite this page - Download PDF

... i ventiduemila abitanti aprivano due volte l'anno le loro porte per accogliere all'incirca centomila visitatori della fiera. Questi arrivano in nave, in carrozza o a piedi; giungevano da Londra, Anversa, Lione e Venezia, ma anche dai villaggi vicini della regione e ogni volta, per tre settimane, trasformavano l'intera vita della città. Come in un gigantesco bazar per strade e piazze, nelle case e persino nei conventi si poteva ammirare sorpreso quanto l'abilità umana aveva fabbricato: i prodotti più scelti dell'artigianato, le invenzioni tecniche più recenti, merci esotiche d'oltremare, dipinti, libri dotti e di attualità come le «nuove gazzette» che venivano esposte o cantate dai loro stessi autori.[1].

Allo storico potrebbe interessare l'emergenza di questa costrizione sistemica alla novità, davanti alla quale la comunicazione religiosa o politica dei secoli XVI e XVII vedrà in essa qualcosa di temerario mentre nell'ambito commerciale sarà d'allora apprezzata al punto tale da essere considerata un motore per l'interscambio. Gradualmente i sistemi religioso e politico invertiranno la loro valutazione negativa per associare alla novità un qualcosa di virtuoso e di necessario. Da l'impressione che i mercati abbiano assorbito più facilmente l'incertezza e la variabilità e sfruttino queste condizioni per muovere l'offerta e la domanda. Invece, per il sistema religioso l'incertezza è percepita solo nei suoi aspetti minacciosi e postula l'equilibrio e la stabilità come valori.

La novità indicherebbe una particolare attenzione verso l'informazione. L'informazione si espone sui tavoli delle fiere dove si apprezzano le nove reperta, ma è anche urlata nel vociare dei venditori delle "nuove gazzette". Questi primi mezzi di diffusione mettono al centro non tanto la questione della verità, con tutti i suoi elementi polemogeni, ma il tema dell'informazione intesa come a difference that makes a difference [2]. L'informazione, per essere tale, dovrà essere nuova. Le notizie dovranno essere soprattutto "fresche". Un caso estremo, ma nondimeno esemplare, di questa scissione tra verità e informazione fu la "guerra delle nove", durante il XVI secolo, che vide coinvolti la Repubblica di Ragusa, Venezia e il Turco.

La piccola Repubblica di Ragusa, tra la fine del XIV e la metà del XVI secolo, è al centro di un traffico molto attivo di informazioni grazie alle quali ottiene uno spazio strategico tra le repubbliche e gli imperi. Nella seconda metà del Quattrocento la Repubblica offre ai re di Napoli, posteriormente a Carlo V e al papa, delle novelle riguardo le galere veneziane e altre novità dei Balcani e dei Turchi. Altrettanto farà con il doge offrendogli qualche turchesca sui movimenti delle navi turche, con la sufficiente cautela per non destare alcun sospetto da parte dal Sultano. Dopo la battaglia di Mohàcs (1526), vittoria di Solimano I sugli ungheresi che implicò un aumento della potenza dell'impero ottomano, Ragusa comincerà a informare in modo più deciso ai turchi sui movimenti navali di Occidente. Il Rector di Ragusa vietò severamente gli informatori privati creando così un vero monopolio dell'informazione. L'informazione più che una comunicazione si convertì in una vera e propria merce di scambio per tener saldo il moto della Repubblica: Non bene pro toto libertas venditur auro; se la libertà non si vende per tutto l'oro del mondo la si può forse assicurare con lo scambio d'informazione.

Non è l'arte dei gazzettanti[4], né i fogli di nove, né il bisogno di conoscere in anticipo le mosse del turco, nemmeno la stampa stessa a generare questo vortice di novità. La sete di novità, che il successo dell'informazione evidenzia, è sintomo di un passaggio epocale di un sistema sociale che si evolve da una differenziazione interna di tipo gerarchico verso una società differenziata funzionalmente. La stampa, in questo passaggio è un fattore evolutivo al suo servizio e trova, in questa congiuntura di progressiva differenziazione, una opportunità per il suo sviluppo. A partire dal XVII secolo alcuni libri scientifici includeranno nei loro titoli la parola novus[5]. All'interno della corrispondenza di Bellarmino può notarsi questa costrizione a selezionare "novità":

Oltre che come mi disse il libraro quando si comprano libri alle fiere in gran numero, i mercanti non hanno tempo di leggerli per intendere ciò che contengono, anzi basta loro di veder dall'iscrizione che sono libri nuovi per muoversi a comprarli per la sola novità de la quale in particolare gli Inglesi sono curiosissimi. Il nunzio di Cologna a Roberto Bellarmino, 20 settembre 1608

Gradualmente i contenuti si dovranno presentare sotto la veste dell'innovazione, si direbbe oggi. L'innovazione così si aprirà lentamente la strada fino ad apparire come una tendenza normale che presuppone una attesa di progresso e di futuro. L'informazione è un indicatore di questa ansia di novità che esclude la ripetizione sulla quale si assicurava il sapere. In questo senso ci troviamo davanti a una trasformazione epocale della conoscenza. Perseguire le novità, al ritmo incalzante delle notizie sempre fresche, implicherà un'alterazione del ritmo della lettura medievale e pertanto dell'apprendimento: Aiunt enim multum legendum esse, non multa (Plinio il Giovane, Epist. 7,9). Potrebbe evidenziarsi qui un capovolgimento della profondità in favore della superficialità. Se una certa tradizione epistemologica indicava che per comprendere era necessario andare al di là di ciò che appare in superficie, con il crescente aumento d'informazioni ci si dovrà orientare velocemente per riuscire a stare a galla ed stabilire il maggior numero di collegamenti possibili. Gli sviluppi di indici, tabelle e marginalia nei testi a stampa potrebbero testimoniare questo cambiamento per offrire al lettore strumenti di orientamento. Questa trasformazione parla anche di un mutamento del significato del tempo in virtù del quale il presente non rappresenterà più l'eternità di Dio in tutti i presenti ma soltanto l'istante che determina la differenza tra passato e futuro.

L'effetto di questa corsa semantica di ciò che è nuovo non lo si riconosce nella forma della concettualizzazione ma nei cambiamenti riguardo l'idea di presente -nel quale soltanto ciò che è nuovo può essere nuovo-. Ora il presente non è più la presenza dell'eternità del tempo e nemmeno esclusivamente la situazione nella quale -in vista della salvezza dell'anima- si può decidere a favore o contro il peccato. Presente non è un altra cosa che la differenza tra passato e futuro.[6]

L'evoluzione del concetto di novitas sta a indicare una catastrofe semantica; catastrofe intesa, partendo dalla sua etimologia (καταστρέϕω="capovolgere"), come cambiamento qualitativo brusco, prodotto da un’ evoluzione graduale e continua. L'eruzione vulcanica può ben rappresentare questa evoluzione inaugurando nuove realtà geologiche e ambientali che si aprono a nuove stabilità. La catastrofe, così concepita, non ha mai un segno univoco: alcuni potrebbero osservare in essa "distruzione" altri "opportunità".

La novità, in quanto schema di osservazione, ha bisogno del contra-concetto di "vecchio". Una crescente valorizzazione degli antichi, dei classici, così come si è registrata per esempio a partire del Rinascimento, permetterà di creare degli spazi per la produzione di novità. Dopo la Rivoluzione Francese si consoliderà questa valorizzazione, utile anche a segnare la frontiera tra Ancien Régime e presente rivoluzionario in vista di un futuro inteso come progresso.

Florilegium

- Gran hechizo es el de la novedad, que como todo lo tenemos tan visto, pagámonos de juguetes nuevos, así de la naturaleza como del arte, haciendo vulgares agravios a los antiguos prodigios por conocidos: lo que ayer fue un pasmo, hoy viene a ser desprecio, no porque haya perdido de su perfección, sino de nuestra estimación; no porque se haya mudado, antes porque no, y porque se nos hace de nuevo. Redimen esta civilidad del gusto los sabios con hacer reflexiones nuevas sobre las perfecciones antiguas, renovando el gusto con la admiración. [7]

- Válgase de su novedad, que mientras fuere nuevo, será estimado.[8]

- [A] Io scuserei volentieri il nostro popolo di non avere altro modello né altra regola di perfezione che i propri costumi e le proprie usanze: infatti è vizio comune non del volgo soltanto, ma di quasi tutti gli uomini, di mirare alla maniera di vivere in cui sono nati e limitarsi ad essa. Mi sta bene che questo popolo, vedendo Fabrizio o Lelio, trovi barbari il loro contegno e il loro portamento, poiché non sono vestiti né acconciati alla nostra moda. Ma mi rammarico della sua singolare mancanza di discernimento nel lasciarsi a tal punto ingannare e accecare dall’autorità dell’uso attuale, da esser capace di cambiar parere e opinione tutti i mesi, se così piace alla moda; e da dare giudizi così disparati su se stesso. Quando si portava la stecca del giustacuore alta sul petto, si sosteneva con argomenti fervorosi che quello era il suo posto; qualche anno dopo, ecco la stecca discesa fino alle cosce: ci si burla dell’altra usanza, la si trova scomoda e insopportabile. L’attuale maniera di vestirsi fa immediatamente condannare l’antica, con una risolutezza così grande e un consenso così generale, che direste che è una specie di mania che stravolge in tal modo il cervello. Poiché il nostro cambiamento in questo è così pronto e improvviso che l’inventiva di tutti i sarti del mondo non saprebbe fornire sufficienti novità, è giocoforza che molto spesso le fogge disprezzate tornino in credito, e poco dopo cadano di nuovo in disprezzo; e che uno stesso giudizio adotti, nello spazio di quindici o vent’anni, due o tre opinioni non solo diverse, ma contrarie, con un’incostanza e una leggerezza incredibili. [C] Non c’è nessuno fra noi tanto accorto da non lasciarsi intrappolare in questa contraddizione, e abbarbagliare così la vista interna come quella esterna senza accorgersene.

[9] - Mi trovavo or ora su quel passo dove Plutarco dice di se stesso che mentre Rustico assisteva a una sua orazione a Roma, ricevette un plico da parte dell’imperatore e indugiò ad aprirlo finché tutto fu finito: per cui (egli dice) tutti i presenti lodarono straordinariamente la gravità di quel personaggio. Invero, poiché egli stava parlando della curiosità, e di quella passione avida e golosa di notizie che ci fa abbandonare qualsiasi cosa con tanta indiscrezione e impazienza per occuparci di un nuovo venuto, e perdere ogni rispetto e ogni ritegno per dissuggellare subito, dovunque ci troviamo, le lettere che ci sono state portate, ha avuto ragione di lodare la gravità di Rustico; e poteva anche aggiungervi la lode della sua educazione e cortesia per non aver voluto interrompere il corso dell’orazione.[10]

- Il gazzettiere si corica tranquillo a sera con una notizia che, alteratasi nella notte, è costretto ad abbandonare al suo risveglio.[11]

- [Varietas]

Además, muy a menudo existe una gran discrepancia entre los códices griegos que ahora se manejan, de ahí que en nuestros tiempos incluso disienten entre sí no sólo en las palabras sino también en las ideas. ¿Cómo es, si no, que a veces esos nuevos traductores no traducen en el mismo sentido los mismos ejemplares? Pues el versículo cuarto del salmo 109 lo tradujeron de distinta manera Lutero, Pomerano, Pelicán, Buzero, Munster, Zuinglio, Félix, Pagnino, de modo que me parecen poquísimas en número la edición de Teodoción, Símaco, Aquila, la quinta, así como la sexta y la séptima y además la vulgata de los Setenta, si las comparas con las innumerables versiones de aquéllos.

¿Cómo es que Erasmo no está de acuerdo consigo mismo? Se conserva, en efecto, su quinta edición y se conservaría la sexta, si no hubiera temido que se le tachara de inconstancia o no hubiera sido impedido por la muerte. Y ciertamente esa variedad de versiones siempre fue para los herejes por así decir familiar y propia. [...] Así pues, esas personas inconstantes más que traducir las Sagradas Escrituras desde las fuentes, lo que hacen es traducirse a sí mismos en torno a las fuentes, e inducidos por diversas y peregrinas doctrinas fluctúan como niños pequeños y son llevados de una parte a otra por cualquier viento de doctrina. Y verdaderamente, cuando alguna novedad salta como un nuevo viento, enseguida se distingue el peso del grano y la ligereza de la paja, y entonces sin gran trabajo es sacudido fuera de la era lo que estaba dentro sin peso alguno.

También se debe temer del cambio [mutatio] mismo de las cosas, pues incluso pequeños movimientos son capaces de perturbar la situación común de los ciudadanos, de tal forma que si se cambiaran los compases musicales -como dice Platón- se produciría un cambio en la República y en las costumbres.

[...] debemos rechazar mucho más aún y temer esa variedad, que es obviamente enemiga de la constancia y la unidad, virtudes que la Iglesia no puede tener si no se da a la par la unidad y el consenso de la Escritura. Bajo este aspecto son más afortunados nuestros tiempos que los antiguos, pues antiguamente se divulgaban tantos ejemplares como códices. Pero en cambio ahora, sin duda por peculiar providencia del Espíritu Santo, por la solicitud de Dámaso, por los esfuerzos extraordinarios de Jerónimo, la Santa Iglesia ha recibido la concorde unidad de las Escrituras y fue quitada de en medio toda variedad, mediante la recepción con el acuerdo de todos de una edición latina única.

Por esa razón, quienes nos remiten a los ejemplares griegos pretenden introducir la misma variedad, de la que antiguamente Jerónimo reivindicó nuestros libros, o más aún, la misma falsedad de la que aquél expurgó nuestros códices. Pues la variedad de códices suele ser ocasión fácil de corrupción. Y aunque ninguna corrupción se produjera, la variedad misma sin embargo es perjudicial, pues nunca puede decirse verdadero lo que es diverso, como escribió Jerónimo a Donenión y a Rogaciano; y, dirigiéndose a Dámaso, afirma: «Con el testimonio incluso de los maldicientes se comprueba que no es verdadero lo que varía. Si, en efecto, se ha de prestar fe a los ejem- plares latinos, que respondan aquellos que tienen casi tantos ejemplares como códices. Por consiguiente, la variedad de ejemplares latinos que entonces había quitaba el crédito en tales ejemplares».

References

- ↑ K. Kroll, Körperbegabung versus Verkörperung. Das Verhältnis und Geist im frühneuzeitlichen Jahrmarktspektakel in Erika Fischer-Lichte, Christian Hornund Matthias Warstat (ed) Verkörperung, 2001, p. 37.

- ↑ Bateson, G. Verso un’ecologia della mente, 1993, Adelphi, Milano.

- ↑ Jean de la Bruyère; Les Caractères ou Les Mœurs de ce Siècle, 33.

- ↑ Sull'origine della "gazzetta" si veda Infelise, Mario; Gazzetta. Storia di una parola; 2017, Venezia.

- ↑ Si veda a questo riguardo Cevolini, A., De Arte Excerpendi. Imparare a dimenticare nella modernità, 2006, p. 54 e ss.

- ↑ Luhmann. N., La sociedad de la sociedad. México, 2006, p. 796.

- ↑ Gracián, El Criticón, crisis III.

- ↑ Gracián, Oráculo manual y arte de prudencia, 269.

- ↑ Montaigne, Michel de., Saggi, a cura di Fausta Garavini e André Tournon, 2012, Milano, Lib. I, Cap. XLIX, Dei costumi antichi.

- ↑ Montaigne, Michel de., Saggi, a cura di Fausta Garavini e André Tournon, 2012, Milano, Lib. II, Cap. IV, A domani gli affari .

- ↑ Jean de la Bruyère; Les Caractères ou Les Mœurs de ce Siècle, 33.

- ↑ Melchor Cano, De locis Theologicis. Lib. II, cap.13.

The text of this page has been reviewed and approved by the Lexicon of modernity (ISBN: 9788878393950 ; DOI: 10.5281/zenodo.1483194) editorial board.

Cite this page - Download PDF